Illusory pattern perception is also less likely to occur in people who are highly educated or very analytic in their thinking. Education level and analytical styles in combination make people less likely to believe conspiracy theories. Higher levels of education are associated with greater cognitive complexity, which makes people more likely to see the nuances of a situation rather than accept a simple explanation for a complex problem. News Literacy Project: Deepfakes, Conspiracy theories The role of education Scientific American gives the example that people who believe Bin Laden was killed years before the US announced it are conversely more likely to believe that he’s still alive. People who are more strongly inclined toward conspiratorial thinking are also more inclined to believe mutually contradictory conspiracies. While social media doesn’t cause conspiracy theories, it does tend to amplify them. feelings of powerlessness, lack of control.

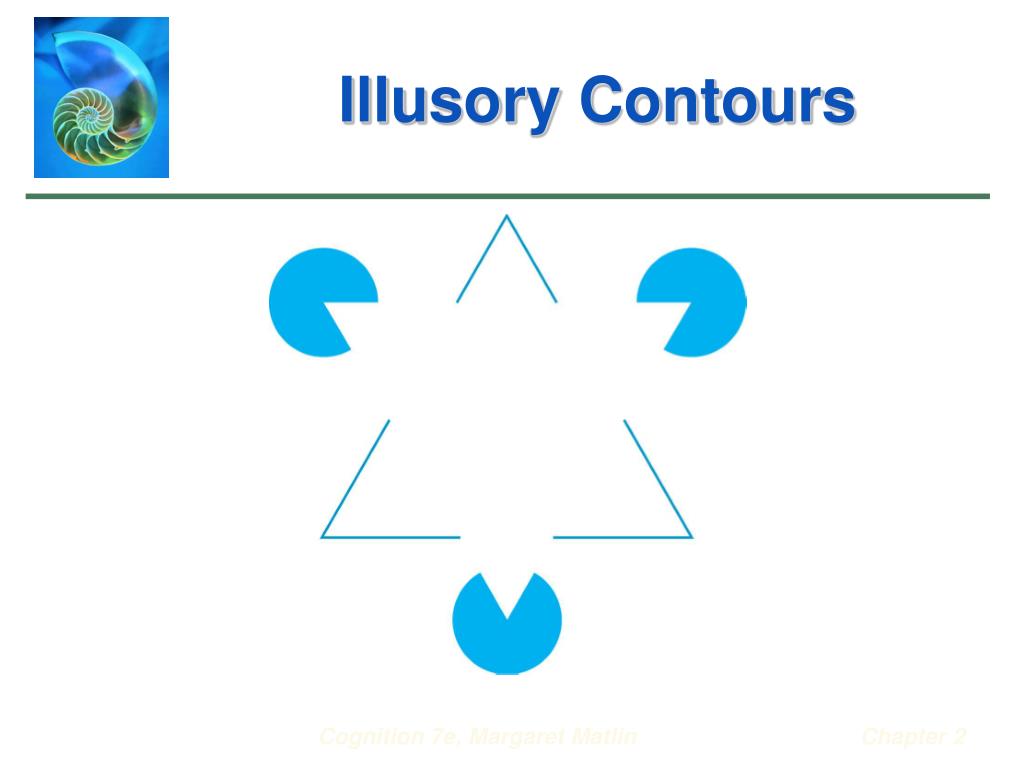

Some of the factors that can promote conspiratorial thinking are: Conspiracy theorizing provides a rather handy way of placing all of the blame for bad things happening on “them”, allowing for the belief that things would be hunky dory otherwise. In anxious, uncertain times, people could accept the idea that bad things just happen sometimes, but that’s not always appealing. Factors that increase conspiratorial thinking A virus mutating as it jumps from critters to humans may not feel like it’s big enough to account for COVID-19, but a conspiracy to transmit it via 5G might feel like a better fit. Proportionality bias means that we expect big, significant events to have big, significant causes. If you already think Trump is the best thing since sliced bread and is being attacked by enemies, Q-Anon is just going further in that particular direction, and it’s easier to stay on the track you’re already on. Our brains try to make things simpler, but the cognitive biases that result don’t necessarily match up with reality.Ĭonfirmation bias means that we tend to seek out, believe, and pay attention to things that are in line with what we already believe. Seeing patterns in chaos but no pattern in structured stimuli was a predictor of irrational beliefs. The study found that both conspiratorial thinking and supernatural beliefs were strongly correlated with each other and with the tendency to find patterns within randomness. The less ordered a situation feels, the more likely it is that people will try to find order where there is none.Ī study published in the European Journal of Psychology concluded that illusory pattern perception is an important cognitive factor involved in conspiracy theories. High-impact, threatening social events make people more likely to look for explanatory patterns. Illusory pattern perception, or apophenia, occurs when we perceive meaningful patterns that aren’t actually there, and then we assume that we can predict the future based on the pattern we’ve just created in our heads. For example, tossing a coin repeatedly might produce results that don’t look as random as it seems like they should be. In fact, we tend to underestimate how often apparent patterns actually happen in random sequences. Our brains like to find patterns, but they’re not that good at differentiating random sequences from actual patterns. Every event is taken as having a specific meaning rather than being random.Any new contrary evidence that comes along is reframed so that it somehow supports the conspiracy theory.The self is seen as a persecuted victim.A belief that there’s still something going on persists even if specific ideas about the conspiracy turn out to be false.Presumed nefarious intent of the suspected conspirators.Simultaneously holding contradictory beliefs.So what makes people buy into the weird and wacky?Īccording to Scientific American, a conspiratorial perspective is “the idea that people or groups are colluding in hidden ways to produce a particular outcome.” The Conspiracy Theory Handbook identified seven characteristics of conspiratorial thinking: Then there’s the variety of nuttiness to do with COVID-19 ( Alliance for Science at Cornell University has a list, including 5G, Bill Gates, the “deep state”, etc.). In particular, the Q-Anon conspiracy theory has become quite popular, despite its utter absurdity. This topic came up in a recent post by Andy of Eden in Babylon. This week we’re looking at the psychology behind conspiracy theories. In this series, I dig a little deeper into the meaning of psychology-related terms.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)